“Facilitated communication” has always been a sham.

***

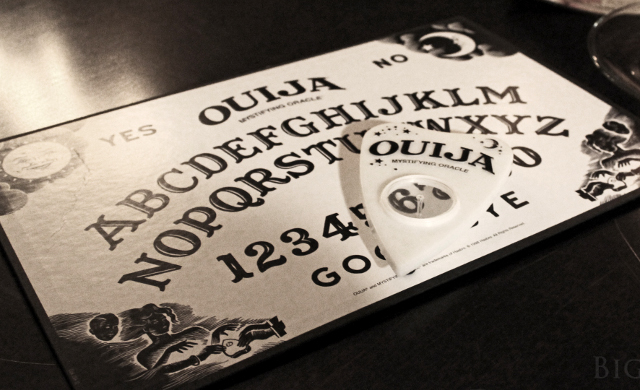

A few weeks ago, David Auerbach wrote a piece for Slate on “facilitated communication,” and I’ve been meaning to write a post about it since then. In case you’re unaware, “facilitated communication” (or FC) is a cross between a fool’s errand and a scam, in which sometimes well-meaning but self-deceptive (and sometimes malicious) people “help” nonverbal disabled people to communicate. This is usually done by “helping” the disabled person to move a finger over a card with letters to spell out phrases. As Auerbach points out, this might as well just be a Ouija board for all the actual communication that’s taking place.

Time and again, the method has been shown to be unreliable to the point where, if people’s lives weren’t so often so terribly affected by the things “communicated,” it would be hilarious. If the facilitator doesn’t know what the person they are “helping” was asked, they are unable to help them answer the question. If the facilitator has not seen the object the person they are “helping” is asked to describe, they are unable to describe it. If the facilitator doesn’t know the answer to a question, neither — unsurprisingly — does the person they are supposedly “helping.”

And yet it has strong adherents, despite the fact that none have yet been able to claim James Randi’s million dollar prize for a demonstration of FC that passes scientific muster. In fact it’s likely their belief in it — despite all evidence — that leads them to fail to realize that the messages are coming from the facilitators themselves and not from their charges. In Auerbach’s piece, the most fervent of true believers seem so confident that at a certain point it becomes simply surreal:

…and because astrology’s not — you know what, nevermind.

Now it’s important to remember the difference between FC and other forms of communication aids in which the intention of the person being aided is actually clear. Naoki Higashida, for instance, the young autistic man responsible for the short but poignant “The Reason I Jump,” has in the past used (and I think still does?) a card with Japanese characters on it for communication — which seems similar to the letter matrices used by FC proponents — but he also types and reads aloud what he has written.

And therein lies the problem. Higashida is incredibly atypical — a nonverbal autistic person capable of overcoming it and communicating with the outside world. He’s exactly the type of success story every FC proponent imagines their client is going to be. Except no-one has ever shown FC to be anything but the wishes of those “facilitators” magnified by hope and the echo chamber of honest-to-god silence from the people they purport to communicate for.

We don’t know they aren’t trying to communicate, but without any evidence to suggest they are, it’s of the utmost importance that we generate actual evidence either way. Otherwise we only end up putting our own words into their mouths, like a bunch of ham-handed ventriloquists.

Go read Auerbach’s piece if you have the time, it’s really something else.

***

Richard Ford Burley is a writer and doctoral candidate at Boston College, as well as an editor at Ledger, the first academic journal devoted to Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. In his spare time he writes about science, skepticism, feminism, and futurism here at This Week In Tomorrow.

One thought on “Facilitated “Communication” | Vol. 3 / No. 5.2”

Comments are closed.