In which, rather than nailing theses to a door and starting a revolution, I post hypotheses to a blog and invite open commentary. This is kind-of a long one, but please, read on.

***

I’m still a little new to teaching at the university level. This is only my fifth year since I started, and one of those years I wasn’t even teaching. I was, in theory, finishing my dissertation, but you can see how well that’s gone (hint: I’m still finishing my dissertation). I started as a teaching assistant for a lecture of Brit Lit 1, then moved on to designing my own syllabi and teaching a class a semester of First-year Writing, Lit Core, Studies in Narrative, and even an elective (Sin and Evil in Medieval Literature, anyone?). I’m a TA again this semester, with forty-odd students to my name, with whom I tease out the finer points of the plays of Shakespeare each week. I say all this so that my colleagues in the teaching world will know what those not in the profession might not guess from that list: I’m still very new to this.

So, keeping that in mind, please bear with me. Perhaps this will come off as naive.

When I read a post this morning by Prof. Jeff Noonan — he’s a philosophy professor at Windsor back in my home province — it made me stop and think (which I’m going to assume was the goal). The post is a list of ten theses ostensibly in favour of “teaching” and against “learning outcomes,” and you may need to go read it for the rest of this post to make sense. I’ll wait.

Back? Excellent. I love repeat visitors.

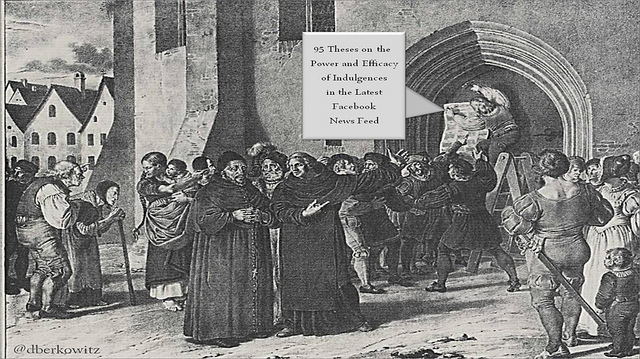

So, for the moment, I think I’ll have to respectfully disagree with some of his positions. Unlike Prof. Noonan who has the seniority to issue theses, I’m going to call my points mere hypotheses. We can test them, and if they’re wrong, so be it. This isn’t about creating a pledge of allegiance for the teaching profession, it’s about positing ideas and seeing where they go.

Hypothesis one: there is no such thing as “true teaching.”

Noonan’s first hypothesis begins with the claim that “teaching at the university level is not a practice of communicating or transferring information but awakening in students a desire to think by revealing to them the questionability of things.” He refers to this in the second as “true teaching,” and describes it therein as “a practice, a performance of cognitive freedom which awakens in students a sense of their own cognitive freedom.” This is a false dichotomy. Teaching, in my limited experience, has been about different things for different students. For some students, I agree, this is true: these bright sparks quickly master the textual content and the methodologies of analysis, and require only the “awakening” of “a desire to think.”

But for some students, the purpose of higher education is not about “awakening” anything, but about acquiring a set of tools — the ability to marshal one’s thoughts into a coherent explanation, the ability to read subtext or identify bias, the ability to navigate an increasingly political marketplace of ideas. These are not “a performance of cognitive freedom,” but rather practical life skills. The ability to read a situation will serve a student long after she gives up on reading Shakespeare.

And let us not sell content short, either: from up on the hill it may seem as though content is only a means to an end, but knowing the raw data — who “poor Yorick” was, what “Machiavellian” means — can in itself act as a means of social navigation. Education is the cultural shibboleth of our times: an understood reference, a unexpected response, these can lead to unlocked doors at key moments. Content-level knowledge can give someone the ability to code-switch in various situations, to seem part of a necessary in-group and grease the wheels of social interaction. The things “everyone knows” carry with them ideas of class, and just being in the know is sometimes a goal.

Because there are multiple kinds of students with multiple kinds of goals — laudable, practical, or even Machiavellian — any definition of “true” teaching must therefore be inclusive of these pluralities. It is for this reason that I posit that “true teaching,” in the singular form at least, is an illusion.

Hypothesis two: the fight over outcome-based learning is a symptom of a systemic issue in the way different people understand value.

In his sixth thesis, Noonan writes that “learning outcomes are justified as proof of a new concern within the university with the quality of teaching and student learning. In reality, they are part of a conservative drift in higher education towards skill-programming and away from cultivation of cognitive freedom and love of thinking.” Again, I must disagree.

Learning outcomes are the unfortunate but predictable outgrowth of the increasing value we have placed on education. From the moment it was decided, culturally and economically, that the singular path to success in life was through higher education, it became inevitable that class-conscious and economically-minded people would try to quantify that value in the primary idiomatic representation of value in our society: money.

Some have tried to answer the question in a post hoc fashion, by charting the lifetime earnings of degree earners and comparing that with their terminal high school diploma earning peers. Having found that there is, indeed, a monetary value to a degree, others have tried to itemize what it is about higher education that confers that economic value, under the mantra that efficiency is the key to optimization: if they can identify the specific traits that confer value, they can address the problem of rising educational costs, which I think all educators should be able to at least empathize with (even if they disagree with the methodology). These “conservatives” are not monsters who don’t understand the “true” value of education, they are pragmatists who are looking at education in a completely predictable, if one-sided way.

Which brings us to “learning outcomes.” All education has intended (and unintended) outcomes. To teach without any intended outcome is, to my understanding, nothing short of poor pedagogical practice. Even Prof. Noonan has an intended outcome: to foster a lifelong “love of learning,” though as he rightly points out, that particular one is hard to quantify. But if learning skills isn’t part of a university education, then I’ve been teaching incorrectly for five years, and I will continue to do so, largely to the benefit of my students. The very division of education into a dichotomy of “love of thinking” versus “skill-programming” is false. Education can and does confer both, and both are valid learning outcomes.

Hypothesis three: the way through this predicament is rooted in empathy and compromise.

The only way I can see through this divide is for both sides of this ideological divide to start recognizing that there are multiple valid ways to measure the value of education. On the one hand, this means that educators will need to be aware of the practical skills they are imparting — which we are, whether we understand that or not. These can be sold to the economically-minded as practical outcomes, and charted in tedious little rubrics if need be. But academics need to understand that we do live in an economy, and that in fact we play an integral, expensive part in its functioning. On the other hand, this means that economists and politicians — the latter of whom are mostly just trying to keep their jobs by trying to quantify a very expensive and very difficult-to-measure societal investment — will need to accept that some of the value of an education cannot be measured in dollars, and that that is something many voters are fine with.

I do not, from my limited experience, think outcome-based learning is being done in a particularly productive way at present. If given too much import, it can limit the ability of educators to elicit the best from individuals, in the name of standardizing a non-standard quantity: our students. It can also reduce productivity, as time spent developing rubrics and standardizing the educational process is time that cannot be spent on actual instruction. Economists will be familiar with this as an opportunity cost.

But that is not to say that our profession ought to be free from goals, some of which at the very least ought to be specific, and ought to relate to the way our students will interact with the society they live in. That means that yes, sometimes we will need to teach measurable skills. But I don’t believe this should be cause for consternation, because we already do teach measurable skills. They just might not be the ones being measured right now.

If you’re still reading at this point, then I commend you for your patience. I don’t know if what I’ve written makes all that much sense, but it’s where my thoughts led me after reading Prof. Noonan’s theses. Let me know in the comments if you disagree, or, if you have a lot of thoughts, write your own blog post and drop the link in the comments.

Thanks again for reading.

***

Richard Ford Burley is a human, writer, and doctoral candidate at Boston College, as well as an editor at Ledger, the first academic journal devoted to Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. In his spare time he writes about science, skepticism, feminism, and futurism here at This Week In Tomorrow.

One thought on “Hypotheses on Outcome-Based Learning | Vol. 3 / No. 19.2”

Comments are closed.