On the week marking the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Beat movement, we have a guest #FeministFriday longread by writer and literary historian Raven See about bringing the women of the beat generation back from a history that fails to see them. Let’s remember them going forward, and place Joan Vollmer and Elise Cowen (and others) alongside Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac.

***

Wednesday October 7th marked the 60th anniversary of the Gallery Six reading, a poetry event in San Francisco that has become synonymous with the birth of the Beat generation. It was there, at 3119 Fillmore Street in 1955, that poet Allen Ginsberg first read his iconic poem “Howl.” A short year and an obscenity trial later, “Howl” was published by City Lights Books in 1956 and undoubtedly ushered in a literary revolution. For me, “Howl’s” power exists in its ability to challenge the status quo in both style and content. The poem disrupts cultural power structures of the 1950s through its unconventional form and its uncensored discussion of topics like mental illness, queer identity, and drug addiction. It is this revolutionary energy that we continue to celebrate 60 years later and is in fact what makes the poem Beat.

Despite its origins of protest, we seem to have culturally repackaged Beat into a dog-eared paperback copy of on the road that fits perfectly into every cis-het, male hipsters’ unwashed levis or flannel pocket. In response to our contemporary moment’s cultural tendency to confine Beat to Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso, I am here to say that the Beat generation is a literary, artistic, and cultural movement that reaches far beyond the boys gang it gets mistaken for. There were women! And while Kristen Stewart, Amy Adams, and Kirsten Dunst certainly offer more nuanced portrayals of “On the Road’s” female characters than Kerouac affords, they were more than characters in men’s lives and novels.

Now let me respond to the first question I always seem to encounter after asserting that there were, in fact, women who can and should belong to this thing we call the Beat generation:

“But who were they? I don’t think I know of any.”

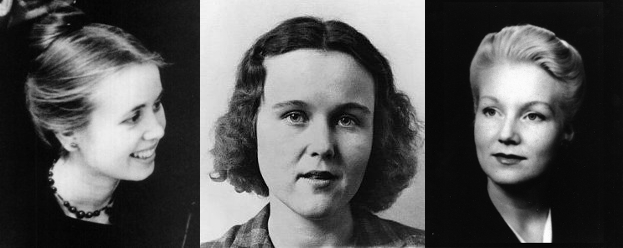

LuAnne Henderson, Joan Vollmer Burroughs, Carolyn Cassady, ruth weiss, Elise Cowen, Natalie Jackson, Diane di Prima, Hettie Jones, Joyce Johnson, Jay DeFeo, Janine Pomy Vega, Brenda Frazier, Anne Waldman, and I promise the list continues. As this is a blog post and not a book, I will only get to talk about some of these women here. So let me include a few resources that will help them to become more than names.

As is often the case when women or other minorities are missing from history, their absence is a myth perpetuated by those who refuse to recognize them. Jack Kerouac described Beat women as girls who “say nothing and wear black,” and Allen Ginsberg infamously claimed there simply were no women writers, or at the very least none worth noting. Despite their countercultural status, many male Beat figures echoed the misogyny that permeated mainstream culture. Gregory Corso offered a more honest portrayal of gender within Beat culture at an event in 1994. In response to a woman in the audience who asked why there were no Beat women, Corso said:

Kerouac could go on the road as his male body allowed him to move freely through space, but also because he had the financial support of his mother. White male privilege isn’t a recent development, and art, literature, and history are all kinds of mixed up in these issues of access and privilege. Beat women sought bohemia as an escape from 1950s patriarchal power structures that stripped them of their agency and personhood. In a world where women belonged to their fathers and husbands, leaving home was a radical act and, as Corso recognized, sometimes a dangerous one. Beat writer Joyce Johnson describes herself and her fellow women as “the ones who dared to leave home,” and I think we have yet to appreciate the historical significance of their courage.

Often disowned by their families for leaving home or pursuing their art, women of the Beat generation sacrificed support and security to lay claim to themselves. A room of one’s own came at no small cost, and these women took jobs as typists, editors, dancers, and models, etc to support themselves. Working by day and creating by night, they learned how to move between the office and bohemia. Beat women could not “drop out” of society in the same way as the men, and in fact, their apartments became places of refuge and their incomes became sources of support for the men who did.

I like to think of Beat women as a kind of bridge to the second wave feminists of the 1960s. While their revolution wasn’t always explicitly political, they were breaking down barriers that were necessary to usher in a world where it was never a question that I could live on my own or backpack across Europe.

Jay DeFeo was the first woman to receive a fellowship from UC Berkeley that allowed her to travel and study art across Europe and Africa for a year and a half. When the committee chose to award her work with the prize, they had mistakenly assumed the artist, “Jay,” was a man. She took the fellowship and traveled to places like Paris, Florence, and Morocco using her experience to inform her art.

ruth weiss and her parents arrived in New York in 1939 after escaping the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. In 1952 she hitchhiked to San Francisco where she became a staple in the art and music scene. For ruth, poetry is linked to music and performance and she began performing her poetry accompanied by jazz musicians. Long before Kerouac would become famous for doing the same, weiss was changing the way poetry was heard. More than an innovative performer, ruth created spaces for art and creation. Like Getrude Stein in 1920s Paris, she hosted weekly poetry and jazz sessions at a club called the Cellar and her apartment became a kind of salon where artists, musicians, and poets would gather.

Hettie Jones co-founded the Beat literary magazine Yugen with her then husband LeRoi Jones. Hettie designed the layout, acted as the magazine’s editor, and constructed it by hand on her kitchen table.

The stories that get told and retold of the Beats in Paris center on Ginsberg, Burroughs, and Corso at the Beat hotel. Burroughs is at the center of any discussion of the Beats in Morocco. Discussions of the San Francisco scene may include Ferlinghetti or Gary Snyder, but they are still dominated by Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and Ginsberg. LeRoi Jones is the artist most associated with Yugen, and sometimes his wife gets a footnote for her help behind the scenes.

It is this kind of blatant erasure that inspired novelist Joyce Johnson to write a memoir about her involvement in the beat generation. In the 1980s, Johnson stumbled upon a GAP add using an image of Kerouac to sell khakis. The picture shows Kerouac standing on a NYC street at night, illuminated by a fluorescent sign. When Johnson saw the add, she was struck by what was missing. The original photo shows a young woman, Joyce Glassman, standing just in the background and looking into the camera. The woman cropped from the photograph is more than a bystander. She is a writer who published her first novel, “Come and Join the Dance,” in 1962. It is a female centric coming of age narrative in which the main character seeks experiences outside of conventional expectation, including taking agency in initiating her first acts of sexual exploration. A woman speaking about her desire to travel on her own and to have sex in 1962 is certainly a radical act, and this novel carries the same revolutionary spirit of many other essential beat texts. It is has only recently returned to publication (and is well worth the read!). Johnson went on to win the National Book Critics Circle Award, to write novels, memoir and biography, and to teach creative writing at Columbia University. Yet when most discussions of the beat generation remember to return her to the picture at all, it is as the one time girlfriend of Jack Kerouac.

Through memoir the women of the beat generation have begun the extraordinary work of their own historical recovery. They did not wait for someone like me to come along and discover the surviving little magazines or texts long out of publication, but instead used their own voices and literary talent to speak their experience. Joyce Johnson published “Minor Characters” in 1987 and if you are looking to learn more about the women who shaped the beat movement, Johnson’s text is the perfect place to start. Johnson uses her writing to reclaim her own voice, but also to introduce us to women who did not get the same chance to speak. Women like Joan Vollmer Burroughs and Johnson’s close friend Elise Cowen are given life in the pages of her memoir. They are more than the wives and girlfriends of famous men they are women with full and complicated lives whose stories are worth telling.

Elise Cowen is a Beat poet who never saw any of her work published in her lifetime. Extremely intelligent and talented, Cowen met Joyce Johnson and others within the Beat scene during her time at Barnard college. She explored her sexuality through relationships with both men and women, she moved from New York to San Francisco, she worked as a typist, she battled depression and psychosis, and she filled notebooks with poetry. Cowen was institutionalized at Bellevue more than once and after a stay there in 1962, she committed suicide. After her death, Cowen’s parents had her notebooks of poetry burned. Shamed by the themes of sexual exploration, mental health, and drug use, they destroyed all but one which survived as it was in the possession of her friend Leo Skir. In an example of how important the work of recovery can be, Tony Trigilio published this notebook just last year, and 50 years later the world can finally hear from Elise:

Sitting with you in the kitchen

Talking of anything

Drinking tea

I love you

“The” is a beautiful, regal, perfect word

Oh I wish you body here

With or without bearded poems

When Ginsberg laments “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” I don’t know if he thought of the women in his life. Fortunately, whether Ginsberg meant to include women or not, the countercultural revolution that followed would. Diane di Prima, dubbed the poet priestess of the Beat generation by scholar Brenda Knight, is prolific poet and performer whose work includes the epic poem Loba, her early Revolutionary Letters, and her memoir Recollections of my Life as a Woman. In her memoir she recounts what is what like hearing “Howl” for the first time:

“The phrase ‘breaking ground’ kept coming into my head. I knew that this Allen Ginsberg, whoever he was, had broken ground for all of us – all few hundreds of us – simply by getting this published. I had no idea yet what that meant, how far it would take us.

The poem put a certain heaviness in me, too. It followed that if there was one Allen there must be more, other people besides my few buddies writing what they spoke, what they heard, living, however obscurely and shamefully, what they knew, hiding out here and there as we were- and now, suddenly, about to speak out. For I sensed that Allen was only, could only be, the vanguard of a much larger thing. All the people who, like me, had hidden and skulked… all these would now step forward and say their piece. Not many would hear them, but they would, finally, hear each other. I was about to meet my brothers and sisters.”

Eventually her sisters would step forward and be heard and they were not afraid to speak about their female experience. Poets like ruth weiss, Anne Waldman, and di Prima herself would continue the work of performing their art. Today you can find 87 year old ruth weiss reading in San Francisco or Anne Waldman traveling cross country performing poetry with her son. Like di Prima and Joyce Johnson, other Beat women came forward to tell their stories through memoir. Hettie Jones would publish the poems she hid in boxes for years alongside her account of her time at the center of the beat movement in How I Became Hettie Jones. Carolyn Cassady wrote her story in Off the Road, Brenda Frazer in Troia: Mexican Memoirs, and Edie Parker in You’ll Be Okay.

In the final sentences of her memoir Johnson conjures another image for us: Joyce Glassman, 22. This time she is not removed from the photograph but “at the table in the exact center of the universe, that midnight place where so much is converging.” Looking back on that girl Johnson writes: “What I refuse to relinquish is her expectancy. It’s only her silence that I wish finally to give up.” Through interviews, memoir, and the continuation of their art, Beat women have refused to be silenced. Their work spans decades and genres and it is now more accessible than ever. It is the work of listening, hearing, and elevating their voices that is up to us. Like most things, history is shaped by the collective cultural stories we tell and it matters whose get told.

***

Raven See is a blogger and independent scholar based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She runs a blog dedicated to the Women of the Beat Generation and is on the board of the European Beat Studies Network. When she’s not writing about literature and culture, you can find her bartending, traveling, or generally tearing down the patriarchy.